- Written by Lonnie

- Published: 20 November 2017

II never intended to overturn the proverbial apple cart. For quite some time I had been told that my direct line of descent ended with a brick wall in the form of a Civil War soldier of uncertain heritage. According to tradition, his grandparents had purportedly come from Virginia by way of North Carolina. When I first set out on this path of discovery, I had only hoped to uncover those early Virginians who had experienced the American Revolution firsthand.

I decided to start by identifying the most prominent 18th-century figures bearing the Colson surname in Virginia and tracing their bloodlines. Almost immediately, I encountered the renown patriot Rawleigh Colston, who famously sold his patrimonial estate in order to outfit a company to fight the British. A book written about the family of his wife, Elizabeth Marshall, sister of John Marshall, the first Chief Justice of the United States, stated unequivocally that Rawleigh descended from William Colston, a brother of Edward Colston, who is known in England today as the Great Philanthropist.

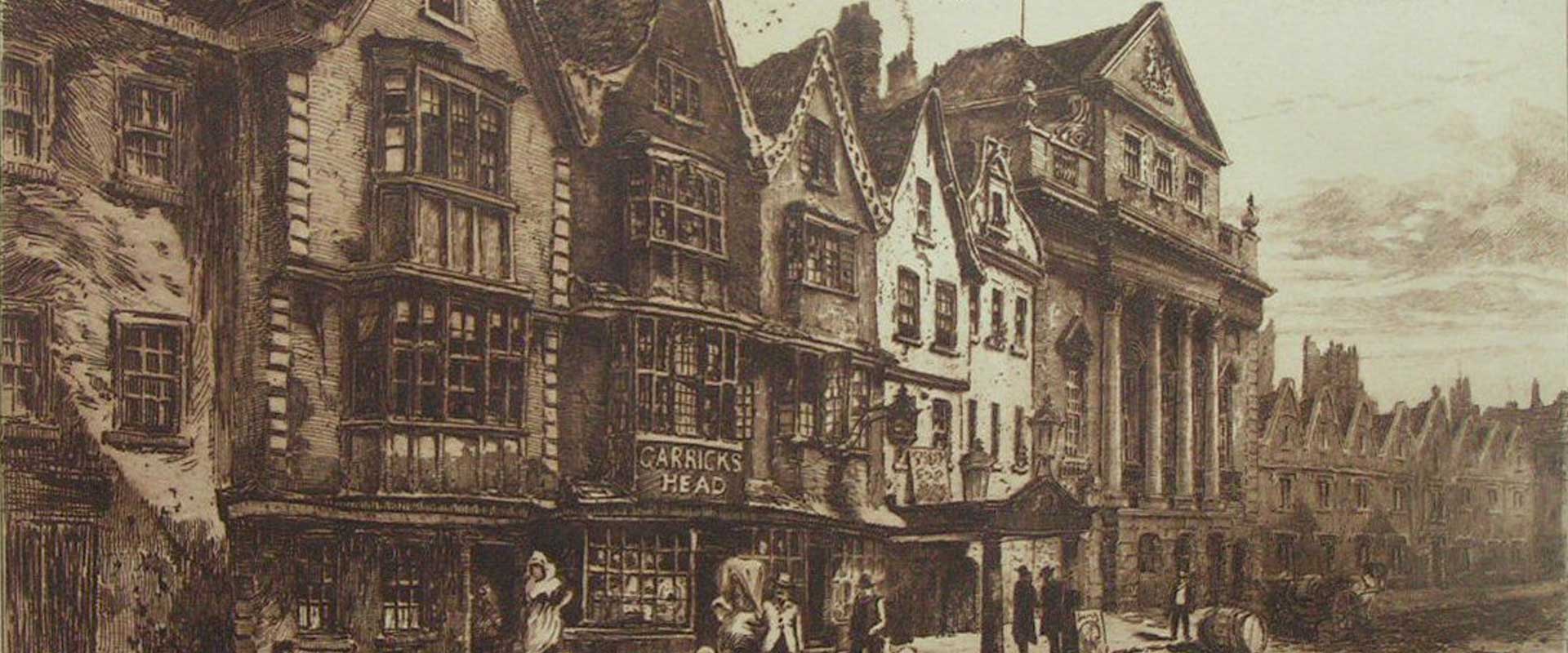

I was ecstatic. I decided to center my search around the family of Edward Colston, Esquire, who was elected to Parliament and possessed of an impressive pedigree stretched back into 16th-century Bristol. Unfortunately, many of these works were published centuries after the deaths of their subjects. It did not take long to locate the Colston family crypt where all of Edward’s family members, including William, lay buried—in All Saint’s Church, Bristol. Historical societies in America faired no better. Publicly-available member applications to the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution reiterate the same blatant errors.

I decided to start fresh and only incorporate information that could be corroborated with period documents. Wills became one of my most vital resources. I spent countless hours translating page after digital page of 16th- and 17th-century handwritten documents. Like the border pieces of a jig-saw puzzle, they helped frame the picture. Family relations were explicitly stated, an absolute necessity if executors were to faithfully follow the originators’ wishes after their deaths. Without such definitive connections, researchers often fall into the trap of attributing ‘scribal error’ to period documents that do not fit into a historical person’s known timeline rather than accept that there are likely multiple individuals possessed of the same name in close proximity.

If you consider that it was the custom in medieval and early colonial times to choose a name for one’s child that was already in the family, it is easy to understand how a researcher several centuries removed could inadvertently combine two people into one. Practically every single generation of the Colston family in Bristol had sons named William, Richard, Thomas, and Robert. While transcribing Wills, there were sometimes three individuals named Thomas who died within the span of a decade. Factor in the added difficulty of finding previously unknown sons and daughters named as legacies and it soon became necessary to create a pedigree chart that would allow for the simple insertion of newly discovered children without requiring any re-ordering of subsequent generations. This manuscript is the product of that revelation.